Since 2018, Germany, France, and Spain are collaborating to develop the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), a sixth-generation air superiority and ground attack system set to enter into service in 2040 (see info box below). Despite ongoing uncertainty about US commitments toward European security – both nuclear and conventional – and a strong push toward European sovereignty in defense, FCAS has been largely characterized by a lack of progress and cooperation. When French President Emmanuel Macron and Defense Minister Sébastien Lecornu visited Germany on July 23 and 24 for talks with Chancellor Friedrich Merz and Defense Minister Boris Pistorius, its fate hung in the balance. Éric Trappier, CEO of French aerospace company Dassault Aviation, recently made controversial comments about France’s role and even suggested FCAS might be bound to fail unless political recommitments are made. As explained in this DGAP Memo, the ability of France and Germany – and to a lesser extent Spain, the third partner – to bring FCAS to fruition will have major consequences for Germany’s defense industry and force planning, as well as for the future of European defense as a whole. The paper closes with recommendations for a constructive way forward.

|

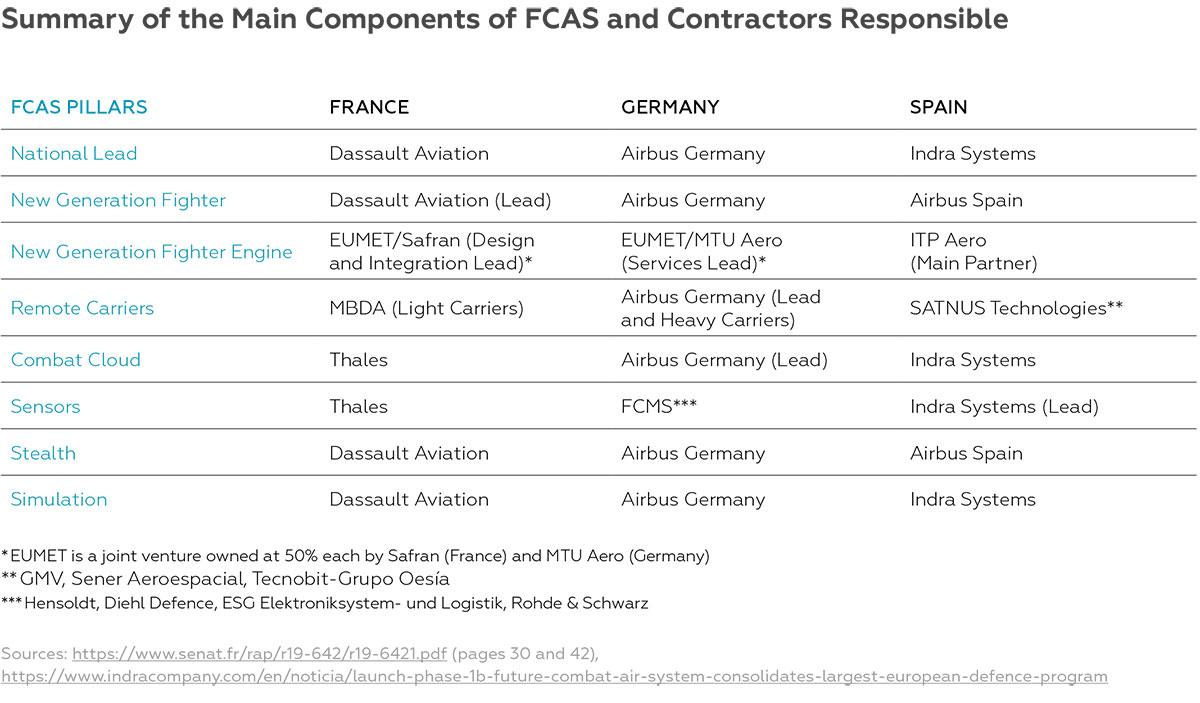

FCAS is meant as a holistic transformation of air warfare emphasizing cooperation among platforms, munitions, and sensors. At its core lies the “system” referred to in its name – one that combines piloted aircraft, sensors, remote carriers (drones), and munitions, all of which share information, data, and tasks. The primary pillar of FCAS – at issue in the present controversy – is the New Generation Fighter (NGF). The development of this combat aircraft is under the lead of Dassault Aviation, the French aerospace company that currently produces the Rafale, a twin-engine jetfighter not only used by French forces but also widely sold internationally. Dassault sees the NGF as the “heart” of the FCAS around which other pillars are arranged. Yet, after Spain joined FCAS in 2019, Airbus Spain was designated as its national contractor for NGF (Airbus also being the German national contractor here), putting Dassault – in its view – in the uncomfortable position of leading the pillar while being a minority partner that could be outvoted by its two Airbus counterparts. The principal German contractor of FCAS – Airbus Germany – leads work on its second pillar, the Combat Cloud, a decentralized, distributed, and delegated information-sharing, command-and-control system meant to integrate sensors, responsibilities, and weapons. It is intended as platform-agnostic, combining manned and unmanned systems, satellite, aerial surveillance, and potentially ground- and sea-based platforms, whether developed through FCAS or otherwise. Furthermore, the Combat Cloud will enable interoperability with legacy platforms such as the Eurodrone, A400M airlifter (and eventually drone mothership), Rafale F5 (under development), and Eurofighter Tranches 4 and 5 (on order). A third pillar is comprised of remote carriers – “heavy” (reusable) or “light” (single-use) unmanned vehicles that operate in conjunction with manned platforms. While Airbus is designated as lead contractor, the French division of MBDA is tasked with the “light” carrier. Meanwhile, Dassault is heavily promoting successors to nEUROn, a European developmental drone project it has led since 2005. For Dassault, nEUROn is both a platform to develop “wingman” heavy carriers for the Rafale F5 and a model of successful European collaboration under its stewardship. |

FCAS in Trouble

In 2022, when FCAS progressed toward its phase of technological development (known as Phase 1B), it already took political pressure to compel the two lead companies – Dassault and Airbus – to agree on a work share. Headwinds against cooperation in the context of FCAS now seem even stronger. In April 2025, Dassault CEO Trappier told the Defense Commission of the French Assembly point-blank that while his company was willing to collaborate – if that was the political command – it also largely possessed the competences to produce the New Generation Fighter (NGF), which France sees as the primary pillar of FCAS, as a sovereign, French-only system. Michael Schoellhorn, CEO of Airbus Defence and Space, retorted that – unlike Dassault – Airbus, the principal German contractor of FCAS, stood for a “more European perspective.” Thomas Pretzl, chairman of the central works council at Airbus’s Manching factory in Bavaria, was uncompromising, arguing that, in Europe, “there are more attractive and suitable partners [than Dassault].”

Part of the disagreement can be explained by diverging perspectives on the program itself. For Dassault, a legacy aircraft manufacturer, the NGF is FCAS’s “heart.” In its view, the other pillars, including remote carriers and the Combat Cloud, serve to enhance the fighter on which the whole project rests – and which is central to France’s nuclear deterrence mission. Consequently, when addressing the Defense Commission in April, Trappier seamlessly switched between referring to the “NGF” and “FCAS” as he claimed Dassault could readily produce a “sovereign FCAS.”

For Airbus, however, as its presentation video makes clear, FCAS represents “The Future of Battle Management” and does not necessarily have a fighter plane as its core. When speaking of the FCAS, Airbus highlights the role of the components for which it is responsible, including crewed-uncrewed teaming and cloud communications, as well as the integration of other Airbus systems. More than France, Germany has an interest in integrating the existing non-FCAS systems it uses, such as the Eurofighter (Airbus) and F-35 (Lockheed Martin), into the FCAS cloud. Furthermore, several of the German defense sector’s key players, not least a budding start-up drone industry, are thriving air systems producers hungry to show their worth. Thus, for Germany, the Combat Cloud and integrated battle management architecture form the cornerstone of FCAS more than the NGF itself. These aspects will also determine the structure of Germany’s immense defense investment and the future of its defense industry as a whole.

Dassault’s grievances are clear: as Trappier has explained, the company objects to the equal workshare among participating countries and contractors, which it argues neuters its ability to lead the program. Therefore, based on the success of the nEUROn drone it is developing, Dassault is strongly advocating for a “best-athlete” model that would allow it to take decisive control of the NGF pillar. In a second stage, Dassault aims to market the NGF for export. A shift from marketing its own flagship model to marketing the product of a jointly-owned program in which each partner would have a veto power could prove complicated – although German Defense Minister Pistorius expressed openness on this point.

Although the latest update of the French national security strategy Revue nationale stratégique (RNS) from July 14 commits France to European procurement, it also requires that France develop its own industrial and technological defense base (base industrielle et technologique de défense (BITD)). During his visit to Osnabrück on July 24, French Defense Minister Lecornu insisted that FCAS is a defense program as opposed to one focused on industrial development. Yet, FCAS will not only create thousands of jobs related to production, but it also has a heavy economic “tail,” meaning the bulk of investments and labor in terms of maintenance, service, and upgrades come after the production phase. Therefore, all partners must reconcile these dual priorities, consolidating national industries, economic benefits, and employment while committing to European jointness. Industrial agreements made today will determine the shape of decades of future heavy investment into the European aerospace industry for the better part of the 21st century.

The Aftermath of France’s July Visit to Germany

During the French visit to Germany on July 23 and 24, there were general claims of a “Franco-German Reset” and a strengthened Europe. Concretely, President Macron and Chancellor Merz tasked their defense ministers, Lecornu and Pistorius, with proposing solutions to remaining conflicts by the end of August – a deadline which Lecornu has since seemed to push back to the fall. On July 24, Pistorius and Lecornu delivered diverging statements. For Pistorius, the current difficulties are “no surprise in large projects” in which “each participant naturally has not only substantial expertise, but also […] their own interests and will.” Nevertheless, Pistorius reiterated that such projects “represent German-French cooperation and partnership, not national egoisms,” claiming that none of the organizational “hurdles” cannot be overcome.

Lecornu was more circumspect. He highlighted the role of states in what is, above all, an armament project rather than an industrial opportunity – a veiled shot at Germany’s demand for guaranteed national work shares. He also stressed the need to resolve problems as a group of three partners to avoid a “dislocation” of European defense and welcomed Germany’s openness toward granting export licenses (without EU involvement). Notably, Lecornu was more noncommittal toward the future of FCAS, whereas Pistorius expressed “no doubts” that Phase 2 – the building of an NGF demonstrator aircraft – would be realized.

Implications for Germany

Options for Germany to move forward on FCAS are limited. Chancellor Merz and Defense Minister Pistorius may choose to partially divest from the NGF – giving in to Dassault’s demands – to safeguard FCAS as a whole. Although such a move would naturally frustrate Airbus, compensation could be agreed upon through guarantees related to production at Airbus’s German center for military air systems in Manching, service, or other pillars of FCAS. Moving forward with FCAS may also require careful adjustment with Spain whose interests have seemingly aligned with Germany’s so far. Yet, for now at least, Spain has remained on the sidelines of what is portrayed as a bilateral crisis.

A second possibility for Germany would be to maintain current working arrangements, albeit with stronger political drive. Dassault is not the only key player demanding political involvement. At Airbus Defence and Space, Michael Schoellhorn also warned that FCAS would be doomed without a strong political push by the end of this year. While a repeat of 2022 – when political leaders compelled a brokered agreement between Dassault and Airbus – would perhaps please no one entirely, it would ensure that FCAS moves forward into Phase 2. Lecornu’s insistence that FCAS is a project among states – with companies as contractors, not leaders – points to this possibility.

A final, more radical possibility may be to forgo a joint NGF altogether. Dassault, which successfully divested France from the Eurofighter in the 1980s, would relish producing another all-French aircraft. Germany – and, potentially, Spain – could then lobby to join the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) led by the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan. Alternatively, Germany could try its hand in another collaborative program, such as with Sweden whose plans to manufacture a successor to its Gripen fighter aircraft are under study. Forgoing the NGF could, potentially, allow FCAS to continue as an open combat cloud system that integrates a variety of European manned and unmanned systems.

While retaining advanced German fighter-production capacity is crucial – both in terms of engineering expertise and industrial output – this could potentially take place outside of the NGF. Restructuring FCAS, as well as developing or reorganizing whichever fighter program Germany would undertake in replacement of the NGF, would, however, cause its own immense political, industrial, and legal challenges. It would also raise similar questions about intellectual property, industrial work share, and program objectives.