Germany and the EU are facing seemingly insurmountable challenges. Donald Trump’s new adminstration has unilaterally undermined the economic, political and security model of the post-Second World War era. At the same time, climate, demographic, and fiscal crises have converged with domestic polarization, economic dislocation, and social alienation to stoke the rise of populist parties. All the while, illiberal actors, such as China, are leveraging their growing economic gravity to overturn the rules-based order. And the degree to which the United States now mimics China’s mercantilist economic playbook suggests – as argued by Michael Froman in Foreign Affairs – that another threat to the international rules-based order is emerging.

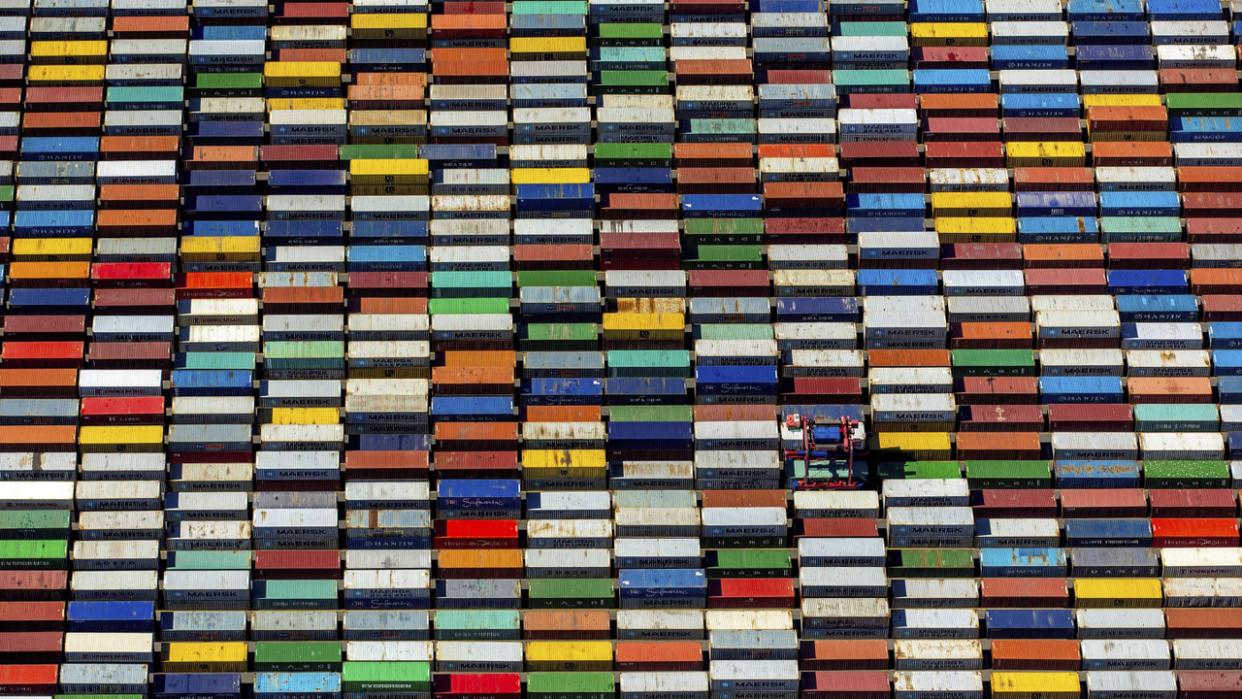

To counter these threats, the remaining family of democratic countries must strengthen its collective economic capacity through inward investment and allyshoring strategies that foster growth domestically and among like-minded nations. These countries need to engage in continuous dialogue and coordination to develop shared strategies that preserve their economic advantage in sectors essential for sustained growth and security. Putting the green industrial transformation at the heart of this would capitalize on a market expected to climb from $2 trillion in 2024 to $11 trillion by 2040. Doing so would also provide democracies with the economic and political strength, as well as the geopolitical resilience, needed to reinforce international stability as major powers create disruptions.

Industrial Decline and the Rise of Polarization

For these partnerships to be resilient in the face of authoritarianism and illiberalism, countries must make investments in consultation with declining communities in former industrial heartlands. These communities brought Donald Trump to the White House twice and have been the strongest supporters for anti-system parties in elections across Europe. Without optimism and opportunities, social frustration and distrust of government will continue to undermine democracies from within. Right-wing movements find fertile ground in hollowed out industrial regions – especially among young male audiences who feel left behind and lack purpose, opportunity, and hope for the future. This has taken place in the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, and elsewhere. Mismanagement of structural economic change, including the energy transition, could make this worse.

Germany’s recent election illustrates the importance of effective industrial transition. In its Ruhr area, the transition from coal and steel is a relative success story. The transition was done on an integrated regional basis in consultation with residents and local leaders. There were investments in new universities, retraining, and social support. As such there has been consistent cross-party political support in the Ruhr area, which has persisted despite elections. In contrast, despite massive investments in the East after unification, the experience of the East Germans was that of West Germany imposing conditions on the populace. This resulted in alienation that has manifested in surging voter support for the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD). The AFD has tapped into this sentiment to undermine the green transition by framing it as a top-down policy imposed by a green political elite from Berlin.

As populists have gotten stronger, mainstream parties have also failed to address broader economic anxiety compounded by a string of crises including a pandemic, multiple wars, a trade war, and nuclear brinkmanship. Germany and parts of Europe aim to address these challenges, but the constraints on decision-making built during peacetime – for example, Germany’s debt brake or the EU’s unanimity voting – are rigid and hinder rapid responses. The competitive edge in manufacturing that laid the foundation for European growth in previous decades has also greatly diminished, especially as China has consolidated leadership in key technologies like renewable energy. Decisive action is required to catch up and will require trade-offs such as looking beyond the transatlantic relationship.

Measuring the State of the United States

The confusing mixed messages from the White House – confrontation one day, retreat and reconciliation the next – have many asking whether it is even possible to engage constructively with Washington, especially on making green tech investments less risky and more attractive for investors. Decision-making seems increasingly focused on Trump’s personal political agenda, the former core leadership of the Republican Party has been purged or silenced, and much of the private sector, particularly big tech, has fallen in line. The current administration has also demonstrated a willingness to stretch executive authority, leverage federal instruments to force compliance, and defy court orders. An erratic trade policy targets friend and foe alike. This conveys a White House that puts immediate political goals above national economic and security interests. Scaling green supply chains with such an unreliable partner brings significant political risk.

But engaging American stakeholders remains critical. The United States is the biggest and most dynamic market in the world and has some of the most dynamic green innovation hubs in the OECD. Established networks with local, regional, and state actors still exist. While these networks might be harder to operate with an anti-climate administration, they can still prove highly constructive – especially those at the regional level that are built on mutually beneficial exchange. Furthermore, Trump’s decisions may continue to vacillate.

Nevertheless, even if these opportunities present themselves, it would not counteract the damage being done to American credibility and clean industry. This uncertainty only reinforces the importance and urgency for Europe, Germany, and other democracies – and even non-democratic countries that want to participate in an open rules-based order – to design their green transition strategies in a way that will strengthen their collective economic and political hand without relying on engagement from the United States.

Pathway Forward

Defense Investments to Bolster Regional Economies

Strong investment in defense can spur economic growth, and as Europe pivots to rebuild its defense industry this could benefit hollowed out industrial regions. Defense-related industries were once central to European economies, and expanding their production can bring economic activity back to declining regions and help reduce disaffection and the appeal of populism. Poland, which is spending 4.7 percent of GDP on defense, is already one example of this. While this is straining public budgets, it is also having a positive impact on growth. Germany could try to strengthen innovation and link ambitions for producing green steel with heightened demand for defense production. If this expenditure is managed in local and regional economies it can revitalize economic centers, especially because these investments are usually very R&D-intensive and can translate into high-level innovation in the civilian sector. Finland and Sweden are two examples where this has occurred.

Enhance Innovation-led Economies

Germany and other European economies are just at the beginning of the China Shock 2.0. Cheap Chinese goods that are expected to flood European markets will cause disruptions across medium and advanced manufacturing. For example, Chinese wind turbines are entering at competitive prices with competitive quality. Meanwhile US tech firms continue to dominate the emerging tech-based business landscape – with these firms now making demands for entry and unregulated access to the European and other markets.

This is a critical priority for Europe if it does not want to be reliant on US tech giants (and resist domination or demands). Europe urgently needs a wholesale group of policy changes to boost speed and scale new innovations and to translate these into commercial products, services, and high-growth companies. This could be accelerated in part through robust public-private partnership-building with like-minded collaborations between business and universities in the US and elsewhere that can share success strategies and collectively build more robust shared innovation ecosystems.

Enhance Allyshoring

China’s dominance across critical supply chains is a major challenge that democratic allies must address together. This requires rewiring supply chains and expanding co-production systems with democracies and other nations that wish to strengthen the rules-based economic and political order. While Trump’s unpredictability complicates this, European partners can still work with others, including Canada, the United Kingdom, Asian allies and other sub-national actors in the United States to strengthen collective economic security and derisk critical technologies needed for a clean and competitive future.

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)/North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is an example of how good, regionalized economic integration can provide strong networks of innovation and collective economic growth. Europe has achieved similar regional benefits through the EU. Despite such strong regional economic integration with key allies, it remains crucial to expand those relationships on a broader, global basis. Over-reliance on a single partner can be a risk, such as Canada’s vulnerability to North-South trade and the likelihood Trump might try to renegotiate USMCA in 2026. For Canada, it will be important to facilitate more intra-provincial trade (east to west) and more trade with other partners (the EU via the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

Allies must prioritize relationships with a wider range of existing and new partners, and these relationships must be addressed in a timely manner. Eight EU countries still have not ratified CETA. We do not have time for such delays anymore, especially when they are held up by interest groups such as farmers. The Latin American common market Mercosur and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are other examples. These trade deals could have been very impactful and would have lowered the EU’s and Canada’s risk exposure to the US trade threat.

Expand Allyshoring and Economy-Strengthening Alliances

Expanding economy-strengthening and allyshoring efforts to leading non-western democracies such as Kenya, Indonesia, South Africa, Brazil, Mexico, and India will be crucial. Many of these regional power centers are disenchanted with Chinese investment and want to diversify their economic cooperation with Europe and other Western democracies. However, the terms of engagement must be carefully articulated to serve both sides’ interests.