| Climate tipping points are approaching critical thresholds. Exceeding them will have abrupt, systemic, and irreversible negative impacts on Germany’s economy, security and population and lead to catastrophic cascading effects. |

| To protect its population and strategic interests, Germany must proactively address the threats posed by exceeding climate tipping points through a systematic risk assessment, strategic foresight, early warning systems, and a coordinated response. |

| Climate tipping points urgently require global cooperation. Germany’s 2027–2028 UN Security Council campaign creates a strategic moment for climate security leadership to win its seat and place tipping points on the Security Council’s agenda. |

Below you will find the online version of this text. Please download the PDF version to access all citations.

Germany faces acute security threats in relation to Russian aggression that require immediate attention. But a reactive approach to security leaves it vulnerable to emerging risks of large-scale systemic disruption. The new German government has deprioritized climate action, seemingly building on the belief that changes are gradual and could be addressed at a later point, once economic and security conditions have improved. This assumption is wrong. In a climate system that is defined by non-linear and abrupt changes, extreme weather events have been materializing beyond worst case scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for this level of emissions. Climate tipping points are one of the risks that carry global implications while threatening Germany’s population and national security. Several of these tipping elements are approaching critical thresholds. Addressing them requires urgent action and international cooperation.

Yet, there is a global governance gap in addressing the security implications of climate tipping points. The UN bodies tasked with the coordination of oversight and protection of the global commons, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) or the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), are facing severe funding cuts due to US withdrawal and a sluggish international response to it. Whereas the US military has previously led efforts in strategic foresight on climate change, these advancements have been stalled, reversed, or actively hindered under both Trump presidencies. On the UN level, Germany and the island nation of Nauru initiated the Group of Friends on Climate and Security in 2018 – also boycotted by the first Trump administration – that brought together countries that push for a stronger inclusion of climate in the UN’s efforts for peace and security.

Addressing climate change as a threat to international peace and security is a central pillar of Germany’s current campaign for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council 2027–2028. This presents a strategic opportunity for Germany to proactively lead on climate tipping points at the international level and win its seat on the Security Council. Moreover, as the United States is stepping away from its responsibilities, Germany has the potential to increase its soft power leverage by taking on a leadership role in the climate security nexus.

On a national level, Germany needs to create systematic risk assessments on climate tipping that feed into its new National Security Council (NSC) and could also underpin the government’s efforts at the UN level. Currently, the climate crisis does not form an explicit part of the newly established NSC, although the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), the Foreign Intelligence Service of Germany, recently assessed that “climate change with its impacts [...] is one of the five major external threats” facing the country. While Germany’s Federal Ministry for the Environment, Climate Action, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety is not included in the round of permanent members of the council, its expertise may be requested for specific topics. This provides a window of opportunity because the NSC claims to also want to assess medium- and long-term risks. In the case of the risks for climate tipping points, effects may play out over longer time horizons, but the need for preventative action is acute.

Climate Tipping Points

The concept of tipping elements in the Earth system describes large subsystems that can approach critical thresholds beyond which they change nonlinearly and irreversibly on human timescales. For example, the Greenland Ice Sheet may see gradual change until a certain point is reached, at which multiple reinforcing feedback loops are triggered and the loss of the ice sheet becomes irreversible. Importantly, these critical thresholds are reached well before the actual collapse or loss occurs, making them impossible to govern without strategic foresight and science-informed decision-making. The point of no return, which translates into a loss of control over preventing this change, can be crossed without imminent and obvious threats to human lives. These materialize over longer timescales as changes, such as sea level rise, accelerate and interventions to stop the change from happening become unfeasible. In fact, when addressing nonlinear changes like exponentially growing damage, limits to adaptation are quickly reached. This was observed during the Covid-19 pandemic during which adaptive measures – procuring ventilators and oxygen – were quickly exhausted when uninterrupted disease spread occurred.

In climate science, these critical thresholds have been expressed in degrees of warming above pre-industrial temperature levels, linking them to the risk assessment that forms the basis of the Paris Agreement. At its core, the Paris Agreement outlines a temperature pathway from 1.5°C to 2°C warming that should not be transgressed. The lower – and for humans safer – limit of 1.5°C will be breached because of lack of political and societal ambition in industrialized countries to reduce emissions. This is often characterized as “overshoot” of the target, suggesting future emissions reductions may be significantly more ambitious than current policies and future overachievement could undo some of the damage that was previously triggered. While, technically, the carbon cycle could be better managed in the future by creating CO2 sinks in addition to decarbonizing, the identification of feedback loops in large sub-systems suggests many changes that are set off during the overshoot may in fact be irreversible.

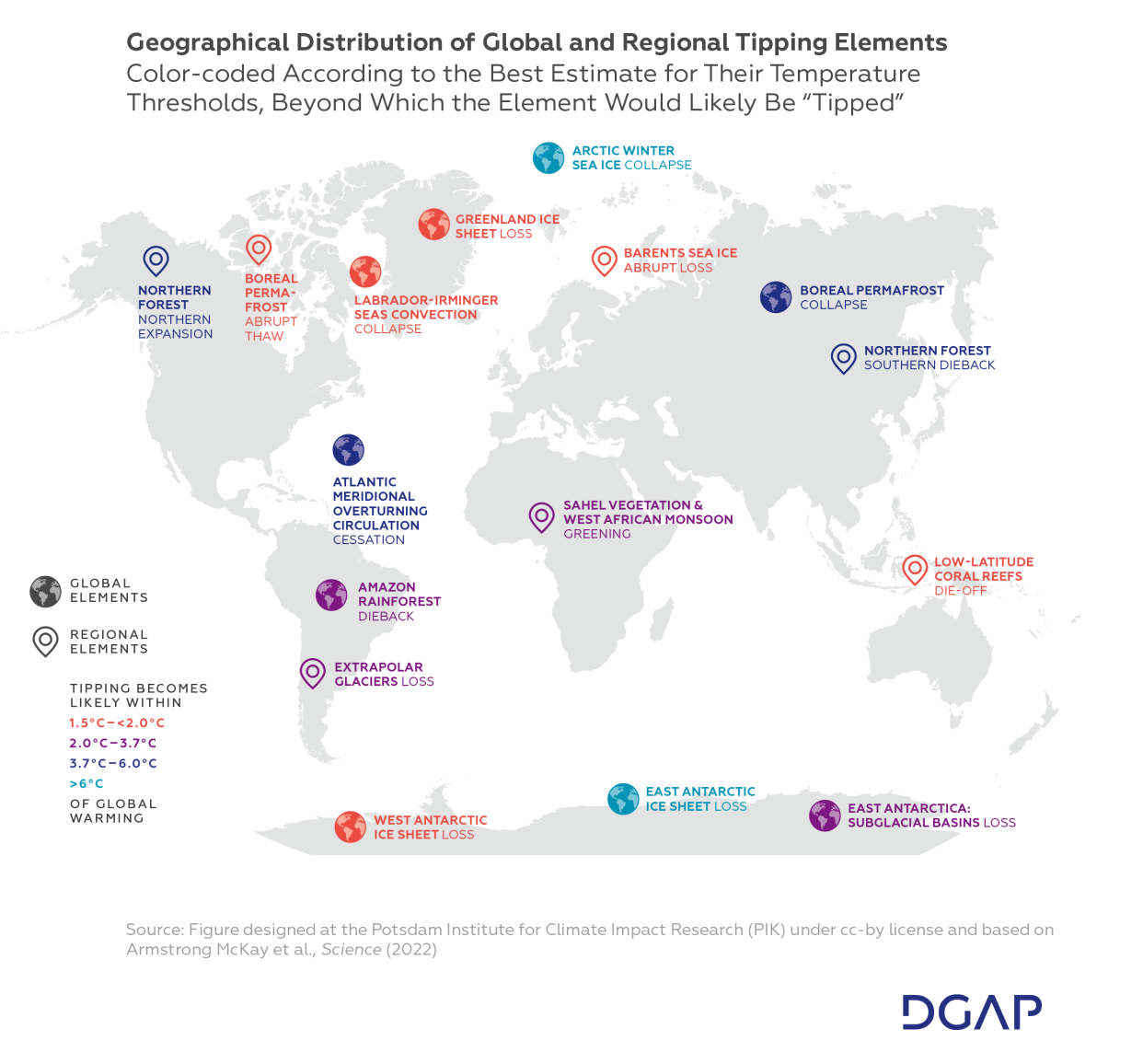

Within the 1.5°C to 2°C temperature pathway, multiple tipping points are already likely to be transgressed, including the loss of the West Antarctic and Greenlandic Ice Sheet that, in combination, commits humanity to sea level rise of more than ten meters; the loss of tropical corals; or the loss of parts of the Boreal permafrost, which releases additional greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Some of these are interlinked and could reinforce tipping cascades, changing several parts of the Earth system. Moreover, systems such as the Amazon rainforest face multiple pressures at once, like deforestation and warming. Hence, low-probability and high-impact events should move further into the core of strategic foresight of security actors.

Security Implications of Tipping Points

The security implications of tipping points are manifold. Additional sea level rise resulting from ice sheet loss would threaten coastal cities, leading to more forced migration and large economic losses. Coral reef destruction will threaten fisheries as many species need healthy reef ecosystems. This will undercut the food security of communities that depend on fish as their main protein source and challenge economic stability. The dieback of the Amazon rainforest could disturb precipitation patterns in southern Latin America and lead to large agricultural losses, potentially sparking displacement and resource conflicts.

Several tipping elements, such as the cessation of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) – and thereby Europe’s heat pump, the Gulf Stream – would likely only occur at higher warming levels. It is, however, important to consider that, while some of these elements may have a low probability of occurrence at lower thresholds, they are highly destructive in their impact. The tipping point of AMOC is somewhere between 1.4°C and 8°C with high uncertainty. Recent studies suggest that tipping of the AMOC may not be as unlikely as previously thought. Unquestionably, higher warming levels increase the likelihood of tipping – a likelihood humanity should seek to reduce as much as possible.

A further slowdown and eventual collapse of the AMOC, of which the Gulf Stream is part, would have far-reaching devastating consequences for Germany and Europe, calling the habitability of some regions into question. In Germany, it would mean that suitability for major staple crops like wheat and maize would plummet. As other world areas would also be affected – for example, through the disruption of monsoon systems – the supply of food through imports would be put at risk. While potential cascading effects for Germany need further research, it is certain that Germany’s national interests would be substantially impeded by the domestic impacts of AMOC cessation and by the consequences of its severe effects on European and international partners. A scenario of mass displacement and decades of food insecurity would not be unlikely. Evidence suggests that the processes leading to the tipping of several elements are already underway and that time to intervene is limited because of the high level of additional emissions released daily.

The Need for Action on a Global Level to Address Security Risks of Tipping Points

Despite scientific consensus and political recognition, policymakers – including in the German government – have not grasped the urgency of the closing window for effective climate action. In part, this is due to a misunderstanding of climate risks that do not unfold in an incremental, linear way but have cascading, exponential effects. The scale of potential damage of tipping points and the capacity to prevent them requires international coordination. No single state can stress the urgency and relevance of adapting international security mechanisms to address emerging global threats posed by climate change alone. The need to shape the Earth system to serve humanity well by fostering environmental abundance, rather than depletion, needs to be at the center of the UN80 reform agenda, which was launched in March 2025 and will soon see operational streamlining and restructuring.

Yet, there is no current mechanism at the international level to address the security risks of tipping points. Although the UNFCCC is the “key instrument for addressing climate change,” its mandate does not cover security issues. While the Conference of the Parties (COP) process has brought incremental progress, the global security order will increasingly be shaped by climate impacts if no sufficient countermeasures are taken. The Group of Friends on Climate and Security, including Germany, have stressed how specific climate impacts such as extreme weather events can threaten human and traditional security. However, this is where the German government needs to make a difference and go further by also pushing for the inclusion of a planetary perspective. It should stress the risks that have layered, global repercussions, which may be less tangible when only perceived on a national scale.

The UN Security Council’s Role

Under the UN Charter, the UN Security Council (UNSC) is primarily responsible for the maintenance of international peace and security. Therefore, it is well-placed to address the security dimension of climate tipping points at the global level. It can take effective action and coordinate a global response due to its powers to make decisions that are binding for UN member states. It can authorize a wide range of measures, including enforcement action.

The Legal Basis for the UNSC to Address Tipping Points

The UNSC’s mandate is tied to the scope of “international peace and security” under article 24(1) of the UN Charter, which limits what the Council can place on its agenda. This scope has expanded over time to encompass diffuse threats such as international terrorism, transnational health crises, and other non-military cross-border threats and sources of instability. The security dimensions of climate change already fall within the Security Council’s mandate. The UNSC has considered climate change in a series of debates and thematic meetings, as well as open and Arria-formula meetings, starting in 2007. However, formal outcomes have been limited to a 2011 Presidential Statement under the German Presidency and resolutions that frame climate change as a driver of conflict and instability in countries and situations already on its agenda. This is valuable but limited to existing agenda items and does not explicitly consider climate change as such – or climate tipping points – as a threat to international peace and security.

Climate tipping points fall within the Security Council’s mandate to maintain international peace and security. In its recent landmark advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice has recognized climate change as “an existential problem of planetary proportions that imperils all forms of life and the very health of our planet” and “underscore[d] the urgent and existential threat posed by climate change.” Exceeding climate tipping points clearly endangers international peace and security and its severe consequences can constitute a “threat to peace.”

How the UNSC Can Use Its Mandate to Address Tipping Points

By declaring in a resolution (as it did for the COVID-19 pandemic) that tipping points are likely to endanger international peace and security, the UNSC would confirm that the security consequences of climate change fall within its mandate. This would give the UNSC the competence to exercise its express and implied powers to address the situation. The UNSC may also investigate to determine whether the risk of tipping points constitutes a situation that, if it continues, is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security and, if so, make recommendations. If the risks posed by tipping points are severe enough, the UNSC could declare a threat to the peace and demand enforcement measures under chapter VII of the UN Charter. Short of this, the UNSC can address tipping points through convening open debates, briefings, or Arria-formula meetings to facilitate an exchange of views among member states; creating a special representative on climate security who regularly reports to the UN Secretary-General, including on tipping point risks and monitoring; and passing a thematic resolution to signal the importance of the issue and call for global, coordinated action.

Challenges

A key challenge lies in the timing and practical activation of the UNSC’s mandate to address tipping points, especially regarding proactive measures against risks whose effects have not yet materialized. The time lag between cause and effect and the low-probability but high-impact nature of these risks necessitates a proactive response – acting early before the risks materialize – which differs from the UNSC’s traditional reactive role in addressing conventional security threats. This reactive approach will fail to prevent tipping points from being breached, leading to irreversible damage. This situation underscores the need to explore how the UN at large and the UNSC specifically can adapt to effectively manage such unprecedented challenges. The situations of terrorism and the COVID-19 pandemic, where the UNSC proactively mitigated risks of endangerment to international peace and security, may serve as precedents.

While there has been criticism of the “securitization” of climate change – including by China, India, and Russia – it is important to recognize that climate impacts, in the absence of emissions reductions, have now progressed to a degree that they are threatening the existence of low-lying coral atoll states and contributing to polarization in many societies. Impacts have also exceeded disaster management capacities in many industrialized countries. Helpless onlookers to flooding tragedies in Texas or Germany’s Ahr Valley are a case in point.

To address global threats, security actors need to gain situational awareness and potentially address fallouts reactively. In cases related to terrorism or pandemics, it is already established practice that they can also engage in risk assessments with civilian institutions that play a more proactive role in curbing risks early on. A similar approach needs to be taken to expected climate impacts. Currently, many national security leaders are practically flying blind in this area.

The UNSC legally can and practically must act early to address climate tipping points. Given veto power dynamics and differing national interests on the UNSC, the main obstacle is political will. It is in the interests of Germany, the five permanent members of the UNSC known as the P5 (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), and all states to cooperate to prevent tipping points being breached.

Germany and the UN Security Council

Confronting climate tipping points through the UNSC strategically builds on Germany’s leadership and innovative approaches to advance climate action in the UN with partner states – such as initiating the Group of Friends on Climate and Security with Nauru and combating rising sea levels with Tuvalu – as well as its significant investments in global climate action. This approach offers a credible way for Germany to deliver on its UNSC election pledge “to tackle the existential threat of the climate crisis and its effects on peace and security” and build on previous mandates. A focus on tipping points at the UNSC also advances Germany’s strategic interests in the short, medium, and long term:

- Short term, it strengthens its bid for a UNSC seat. It differentiates Germany’s campaign from the more general climate pledges of its competitors Austria and Portugal; demonstrates the concrete value it would bring to Council membership; and presents a vision to modernize the UNSC without the need for formal reform (which is unlikely). Importantly, it gains support from the countries of the Global South, a key UN voting constituency that is most affected by climate change.

- Medium term, it positions Germany as a global leader in a moment of geopolitical chaos and UNSC deadlock, deepening international cooperation and enhancing foreign policy collaboration with other nations to protect the climate and other strategic interests.

- Long term, it mitigates the catastrophic consequences of climate tipping points that would eclipse current crises in their effects on peace and security, as well the economy.

There is strategic value in advancing this agenda even without a binding UNSC resolution. Doing so brings international attention to the issue, raises awareness of the risks, establishes precedent, and advances the political debate. It lays the foundation for when political positions and the geopolitical situation – and climatic conditions – change.

Policy Recommendations

Tipping points are an external threat to German national security, and a coordinated international response is required to effectively address them. Therefore, the German government should take up this topic in two ways: domestic and international.

Integrate climate security into the risk assessment of non-hostile systematic threats through the National Security Council’s strategic foresight division:

- The leadership of the German Federal Foreign Office will form part of the National Security Office while retaining in-house expertise on the climate security nexus. Therefore, it would be well placed to highlight the foreign and national security policy dimensions of climate tipping.

- The NSC should be regularly briefed by scientific advisory boards such as the Advisory Council on the Environment, the German Advisory Council on Global Change, or the Advisory Board on Civilian Crisis Prevention and Peacebuilding on the security risks of climate change. These briefings should include a yearly update on the state of tipping points in the Earth system to build operational awareness of the fundamental changes underway.

- Climate science should be linked to strategic foresight and a security risk assessment at the strategic level to monitor developments and anticipate and mitigate consequences for German security and develop a coordinated cross-government response. This can incorporate scenario building to test institutional responses and increase preparedness. For example, the 2026 LÜKEX exercise on heat extremes is a step in the right direction. However, a scenario in which multiple climatic stressors occur at once and affect Germany’s internal and external security still needs to be considered.

- Establish monitoring mechanisms for ongoing assessment and early warning by scientific institutions together with policy-oriented think tanks and advisory boards in Germany. Ministries working on climate and environmental security – such as the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Climate Action, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety and the Federal Foreign Office – should design funding streams that assess risks of threshold crossings on multiple timescales. As the United States withdrew support for the IPCC, Germany should use its leverage to foster a closer assessment of low-probability high-impact events and summarize their potentially cascading effects on human systems.

Seize the opportunity to advance climate tipping points on the agenda of the UN Security Council:

- To win the UNSC seat (and avoid the domestic political setback of a loss), German leaders must show political commitment to Germany’s UNSC pledges. These include its pledge to “tackle the existential threat of the climate crisis and its effects on peace and security.” The sincerity of this pledge is unconvincing if this issue is deprioritized domestically and excluded from the NSC.

- Germany can strengthen its UNSC campaign by highlighting tipping points in its climate messaging in campaign materials, bilateral meetings, and speeches at the UN General Assembly and other high-level fora. It can also showcase its commitment and expertise by hosting a UN panel on the cascading impacts of tipping points.

- In coordination with like-minded countries, Germany should prepare and publicly advance its legal interpretation of article 24(1) of the UN Charter to encompass climate tipping points as a threat to international peace and security. To achieve consensus on this topic, including among the P5, it should plan diplomatic efforts and engage in awareness-raising campaigns using the scientific briefings and monitoring mechanisms referred to earlier to inform its positions and advocacy.

- Once elected to the UNSC, Germany should use its rotating Presidency to convene open debates, briefings, and Arria-formula meetings on climate tipping points and their consequences for global peace and security. It should propose a thematic resolution or Presidential Statement that recognizes tipping points as an endangerment of international peace and security and call on the UN Secretary-General to monitor and periodically report to the Council on their security implications.

- Whether or not it is elected to the UNSC, Germany can exercise global leadership by bringing the situation of climate tipping points to the Security Council, requesting an urgent meeting of the Council and seeking recommendations to address tipping points as an endangerment to international peace and security.

Acknowledgments: This research is supported by the British Academy’s Global Innovation Fellowships Programme, an initiative of the UK Government’s International Science Partnership Fund.