Please note: Below you will find an executive summary and the introduction contained in the policy brief. The complete paper can be downloaded as a PDF here.

Summary

| Ranked alphabetically, the most ambitious countries in quantum computing are Australia, Canada, France and Germany, as well as the UK and the US, followed by Japan and South Korea. Trailing behind are Denmark, Ireland, and Singapore. |

| In post-quantum cryptography, Germany leads jointly with Australia, Denmark, France, Ireland, and the US. Japan, South Korea, and the UK closely follow. Romania and Singapore are some way behind. |

| The US is the most frequently mentioned partner (8) in the analyzed national quantum strategies, followed by the UK (6), and Germany (4). Ireland, Romania, and Singapore are not mentioned in the national strategies analyzed. |

| To propel quantum innovation, Germany should establish a Quantum Benchmarking Initiative within its new Digital Ministry. This would help German and European companies verify and validate their progress with quantum computing. |

Introduction

Quantum technologies are rapidly emerging as a cornerstone of technological competitiveness and national security. Quantum computing and post-quantum cryptography offer transformative capabilities, from resolving complex optimization problems to enabling ultra-secure communications that are resistant to cyberthreats. These advances have significant geopolitical implications that are driving governments worldwide to develop comprehensive national quantum strategies.

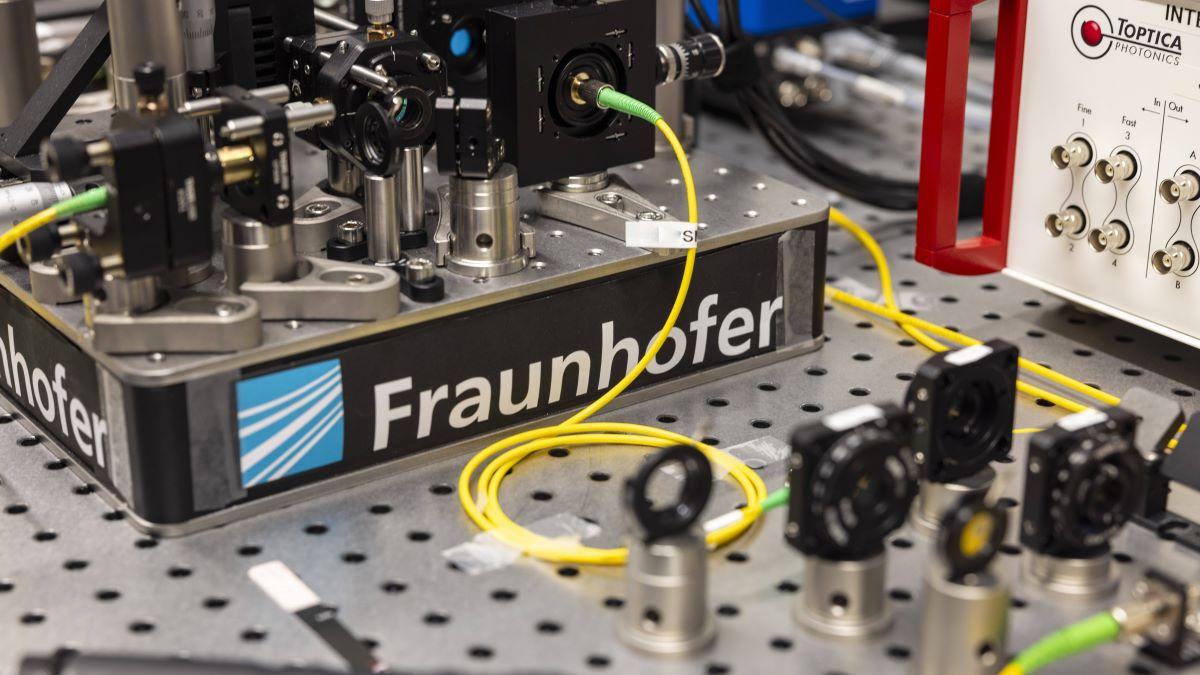

Developments in quantum technologies are especially important for Germany, since, in contrast to developments in artificial intelligence (AI), it is among the leading countries in the race to develop such technologies. Germany has the potential to profoundly shape developments in quantum technologies and a first mover advantage in deploying these across its important manufacturing sectors, thereby unlocking additional economic growth.

In recent years, leading economies — from the European Union and its member states, such as Germany and France, to the United States, and China — have launched substantial initiatives to gain a competitive advantage in quantum research and development. Germany, for instance, invested €2 billion in quantum technologies between 2020 and 2024. The US, for its part, passed the National Quantum Initiative Reauthorization Act in 2024, which allocated $2.7 billion in federal funding over five years to advance quantum research and development in federal agencies. Similarly, the European Union’s Quantum Flagship program, launched in 2018 with a budget of €1 billion, fosters collaboration among research institutions, industry, and governments across the EU member states.

An increasing number of countries have published national quantum strategies in recent years. These documents vary in scope. Some prioritize research and development while others emphasize industrial competitiveness or military applications. As quantum technologies are deployed increasingly to tackle real-world challenges, national strategies will play a critical role in shaping the direction of their development. An understanding of these policies will be essential if stakeholders across government, industry, and academia are to navigate the emerging quantum landscape effectively. This policy brief analyzes how Germany’s quantum ambitions compare to those of other countries, and whether those countries perceive it as a leader in the field.

Methodology

This policy brief analyzes the ambitions of Germany and ten other countries as outlined in their published national quantum strategies.[4] Ambition is analyzed using two variables: the most powerful quantum computer a country is planning to build on its territory by a certain year and when that country aims to transition to post-quantum cryptography.

The policy brief does not examine all major countries: To the authors’ knowledge, neither Russia nor China has published a national quantum strategy document. They were therefore omitted from this study. Nor do countries that already have initiatives, such as “Quantum Austria” or India’s “National Quantum Mission”, fall within the remit of this study. Where we identified that a country has published a quantum strategy, we also consulted other sources on that country’s quantum ambitions, such as initiatives and documents, the websites of companies that operate on their territory, and media articles related to the country. This was done to address information scarcity, such as where the initial strategy only mentions the country’s post-quantum cryptography ambitions and its international partnerships, but not its quantum computing goals. For example, the British National Quantum Strategy (2023) does not set out its ambitions regarding quantum computing power, but these are set out in the UK National Quantum Technologies Programme.

When describing the power of quantum computers, most countries’ strategies mention qubits as a benchmark of performance. Some countries also go into more detail by specifying whether they mean physical or logical qubits. A logical qubit comprises a group of physical qubits. This is a low level of precision for assessing ambition, but it is the level of precision that most country strategies provide. There is often no mention of gate fidelity, error correction capacity, or the type of hardware platform, which are all essential aspects of running a powerful quantum computer. The policy brief therefore relies on qubits as a benchmark for how powerful the planned computer will be.

Regarding the transition to post-quantum cryptography, countries are vague about the infrastructure they aim to transition to post-quantum cryptography by a certain year. The UK , for instance, states that it aims to transition high-priority systems by 2031. Australia intends to ban certain weak algorithms by 2030, which makes it a crucial date in its post-quantum cryptography transition. Despite their different approaches, we take both Australia’s and the UK’s examples as indications of when they aim to transition.

Finally, we assessed whether a country’s ambition is commensurate with its international reputation. Germany might be very ambitious, for example, but other countries may not believe in its quantum capabilities. To assess international quantum reputation, we analyzed how many countries mention in their strategies a desire to partner with Germany. We also examined how this compares to the number of countries aiming to collaborate with the US or the UK, among others.

As far as possible, we have aimed to explain technical terms in layperson’s terms in the main text. If more detail is required for further contextualization, however, it is provided in footnotes.

Download the full policy brief here.